Tear sheet from Courier-Journal microfilm, May, 1954. Read more about the case here.

Blogger’s note: This post was originally published in the Courier-Journal on Sept. 28, 2014 and edited by Pam Platt.

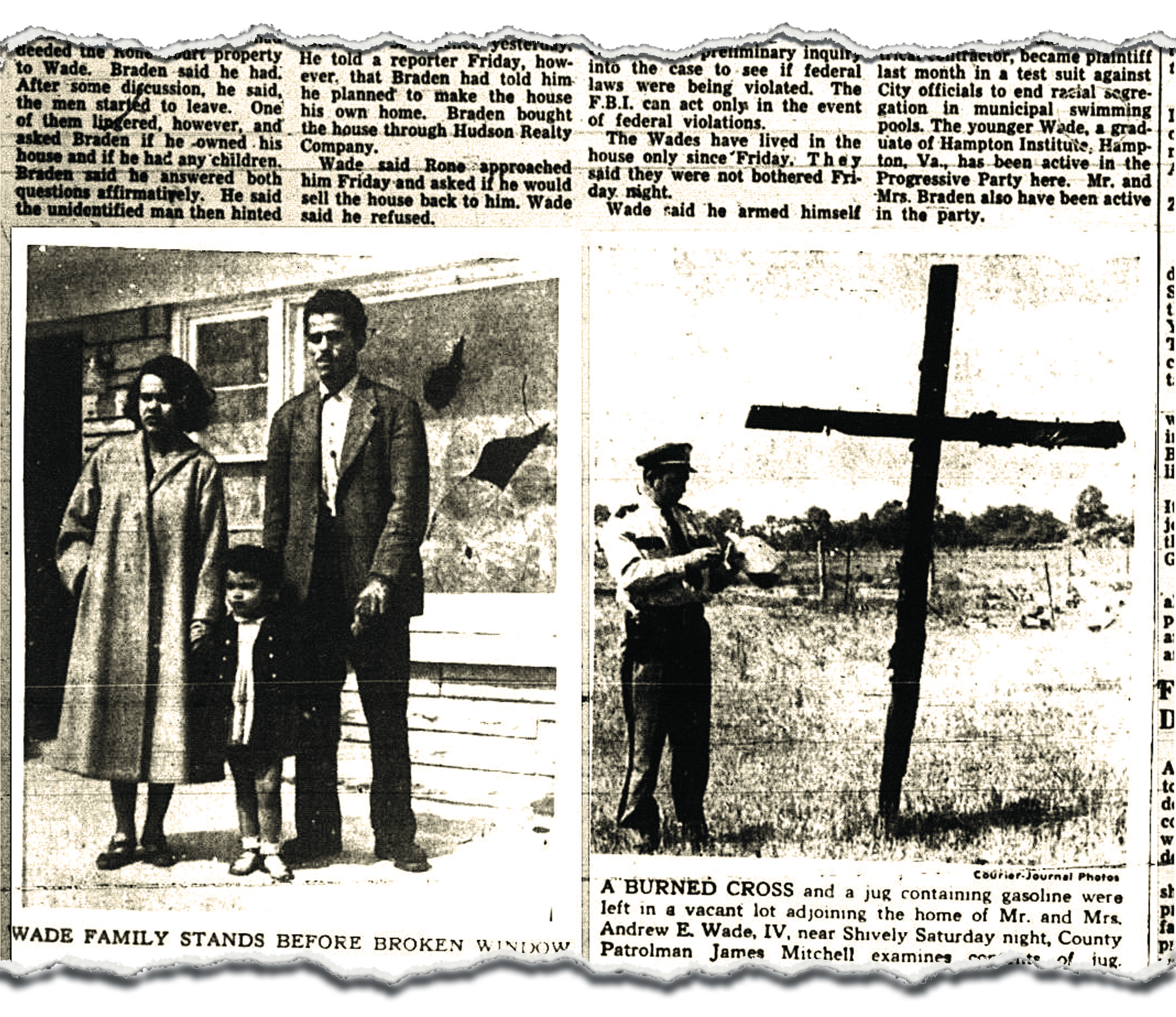

For the past several months, as staff at the University of Louisville Anne Braden Institute for Social Justice Research, I have been compiling newspaper clippings, archival photographs and other artifacts for the exhibit “Black Freedom, White Allies, and Red Scare: Louisville, 1954.” At its most basic level, the exhibit is about events and circumstances surrounding the home that militant white anti-racism activists Anne and Carl Braden purchased in 1954 in an all-white neighborhood on behalf of Charlotte and Andrew Wade, an African-American couple. More broadly, the home purchase, its dynamiting and the subsequent prosecution of the Bradens are about race, media and scapegoating.

But on a deeper, more personal level, it’s about the defense of black womanhood and the black family.

As we reached the final stages of exhibit planning, I began to frame the events of 1954 around Charlotte Wade, a black woman and homemaker. According to Anne Braden’s recollection in her memoir, “The Wall Between,” Charlotte wasn’t an activist like her husband, Andrew, was. She didn’t run in progressive integration circles or have a mission to end racism or to otherwise radically change society. She had a vision for her life that included living in the home of her choice, and her husband wanted to give her dreams to her.

There’s a moment in “The Wall Between” when Anne Braden suggests to Andrew that he and Charlotte select a house near her and Carl, in a western Louisville neighborhood where a number of black families had moved in and a few whites had opted to stay (rather than “fly” to the suburbs for fear of decreasing property values). Andrew told her no, because to remain in the city wasn’t what Charlotte wanted. And as he would tell reporters in the days after a cross was burned in front of the dream house, he would not move because “I would not be doing justice to my wife who loves the house or my children who are entitled to the best.”

It’s not the little romantic in me that swoons at those words. It’s the everyday me, the black woman who says she doesn’t internalize the Eurocentric standards of beauty upheld on screen and in print, but who cheers relentlessly for Lupita Nyong’o and who was high-fiving herself during Michelle Obama’s acknowledgement at Maya Angelou’s funeral of the beauty of black women. The black woman who shudders every time she comes across something about Sarah Baartman. The one who carries awareness of the objectification, dehumanization and hypersexualization of black women everywhere she goes. The one who studies civil rights and Black Nationalist movements and knows black women are erased from their histories. The one who knew the Twitter trends #SolidarityIsForWhiteWomen and #BlackPowerIsForBlackMen spoke ugly truths. To the everyday me, thoughts that a black woman’s wishes drove the home purchase that eventually ignited a nationally captivating trial — and that a black man dared to transcend social boundaries to fulfill her wishes — are empowering.

Sure, I could cite other motivations. Andrew Wade might’ve gone forward with all of it just because he felt masculinity’s pull to provide for his family and pride at the fact that he could give them what they wanted. His activist inclinations may have been more of a factor than Anne Braden indicated. But I have to believe Andrew Wade wouldn’t have taken the risks he took if he hadn’t loved his wife.

I see Charlotte Wade as a woman who wasn’t afraid to say what she wanted and who didn’t see why the inferiority that others projected onto her because she was a black woman should stop her from obtaining it. She didn’t succumb to the expectation that black women provide unreciprocated support, that their needs and desires follow everyone else’s. In a culture where black women’s very existence was scorned, Charlotte Wade effectively declared, “I deserve better.” And her husband and the Bradens defended her acknowledgment of her self.